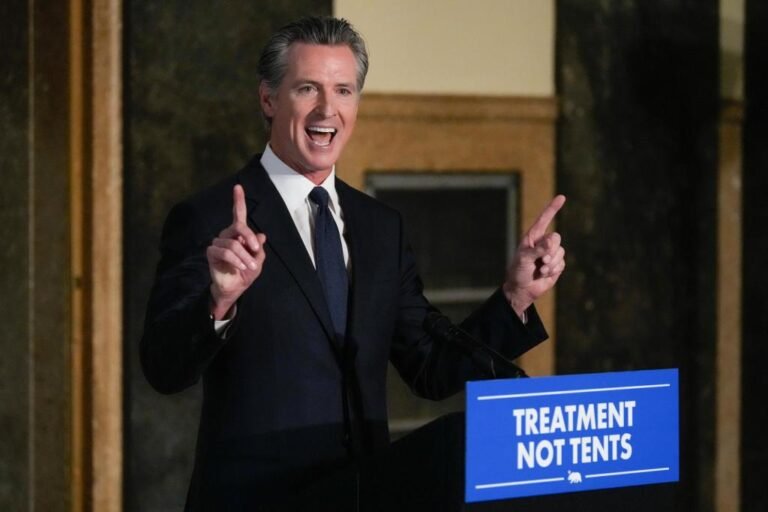

FILE – California Gov. Gavin Newsom speaks in Los Angeles on Oct. 12, 2023, before signing two major bills to transform the state’s mental health system and address the state’s worsening homelessness crisis. Talk about the mental health crisis. About 100 petitions Newsom created a bill to quickly direct people with untreated schizophrenia and other psychotic disorders into housing and medical care under the Alternative Mental Health Court program, which could be filed in December 2023. As of January 1st, it has been filed in seven California counties. (AP Photo/Damien Dovarganes, File)

Gov. Gavin Newsom’s $6.4 billion plan to get thousands of homeless people off the streets and into treatment received strong support Wednesday from conservative voters in rural counties ahead of Election Day. He appeared to be on life support after outright rejecting a visible mental health ballot measure.

The vote in favor of the measure remained just above 50% as mail-in votes were still being counted. A simple majority is required for passage.

“There were warning signs in the polls, but this was still a surprise,” said Thad Kousser, a political science professor at the University of California, San Diego. “Voters remain concerned about homelessness, but remain skeptical about spending to address homelessness.”

If approved, Proposition 1 would approve bonds for an estimated 11,500 new treatment beds and homeless housing units. The two-part measure would use funds already in the mental health system to expand intensive care programs and build supportive housing. We could accomplish both without raising taxes. According to the nonpartisan Legislative Analysis Service, it would cost the state about $310 million a year over 30 years to pay off the national debt.

A February poll conducted by the Public Policy Institute of California ahead of Tuesday’s election showed that 59% of likely voters supported Proposition 1. That’s a significant drop from the 68% support the nonpartisan research group found in December. Historically, voting measures tend to lose support leading up to Election Day, often as opponents’ messages become more aggressive.

Another factor working against Prop. 1: It came during a primary election with low turnout. That means a higher share of older, less diverse voters tend to be wary of big-ticket spending measures, especially as states face budgets this year. A shortfall of tens of billions of dollars.

Still, while early reports showed that the most densely populated coastal counties, including most of the Bay Area, supported Prop. 1 by clear majorities, support generally fell short of what polls showed. It was lower than it was. In San Francisco, where street homelessness poses a particularly sticky problem, early voting results showed more than two-thirds of voters support the proposal.

Meanwhile, nearly all inland counties that tend to be politically conservative opposed the bill, some by large margins. “This is more of a Republican and anti-tax vote than anything else,” Kousser said.

For example, early results show Santa Clara, San Mateo, Alameda and Contra Costa counties have 55% to 60% support for the measure. San Bernardino and Fresno counties, the largest in the Central Valley interior, had 54.5% and 56% opposition, respectively.

On the coast, just over 50% and nearly 58%, respectively, opposed the bill in San Diego and Orange counties, both of which lean politically moderate. Farther north, there were close races in Ventura, Santa Barbara and San Luis Obispo counties.

Political experts said the rural-coastal divide reflects a long-term trend of increasing polarization in the country. But while some conservative lawmakers and disability rights advocates have expressed concerns about increased spending and increased use of involuntary mental health detention, the relative lack of opposition has led to Given this, they added, the bill’s poor performance across the state remains somewhat surprising.

In fact, even many Republicans supported the bill, including state legislators and the mayors of Stockton, Fresno, and Bakersfield. The Prop. 1 campaign also far outspent its opponents, spending millions to fund television ads showing the governor pleading with voters to pass a measure called “Treatment, Not Tent.” collected. According to election filings, the “No” campaign raised just $1,000 in donations.

But Newsom’s support may have suffered, as many Californians feel uneasy about the state’s direction.

“This campaign was centered around the governor,” said Mark Baldassare, a pollster at the Public Policy Institute. “And our poll shows the governor’s approval rating at 48%.”

Failing to pass this bill could be a political embarrassment for Newsom, but the state’s mental health system will need to be strengthened through other new policies that force treatment for homeless people with serious mental illnesses. It would also be a setback for his broader efforts to overhaul the country.

Despite unprecedented billions of dollars spent to curb homelessness in recent years, the state has an estimated 181,000 unhoused residents. But experts say only a small percentage of people are mentally ill enough to not meet their most basic needs.

Dan Schnur, a political science professor at the University of Southern California and the University of California, Berkeley, said the bill’s prospects could dim if results continue to trickle in, as thousands of mail-in ballots have yet to be counted. said.

“If we get closer to the election, that’s bad news for the ‘yes’ side,” Schnurr said. “Older voters and suburban voters tend to vote by mail more than other voters.”