The Foundations of “Hinduism” in the Sufi Epics

Medieval society was extremely diverse, stretching far beyond the reach of courts and cities. Pastoralists, wandering merchants, mystics, artisans and farmers made up a large part of the population. The town of Dalmau, which today lies between the urban centres of Kanpur and Prayagraj, was once dominated by Ahir pastoralists before it was conquered by the Delhi Sultanate.

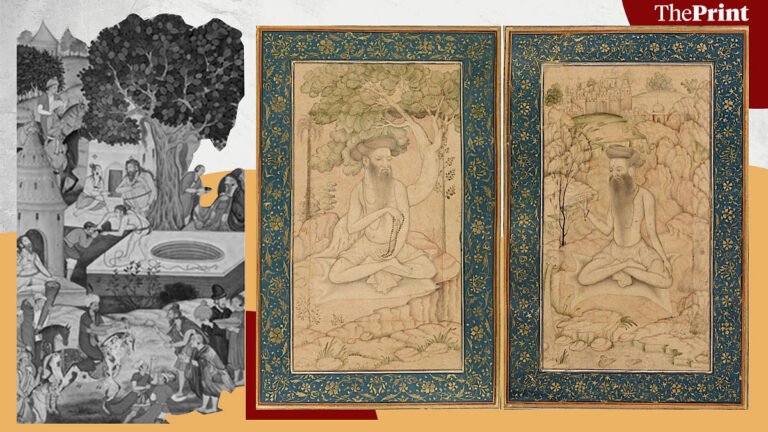

In the second half of the 14th century, as the Sultanate of Delhi was replaced by smaller regional sultanates across North India, astonishing new Islamic texts appeared in the historical record, many of which were written by Indians who had sought initiation from Sufi masters. One of these texts, perhaps one of the most important written in North India, is the ” ChandayanIt was written by Maulana Daud, an Ahir herder turned Sufi. “I threw my sins into the Ganges,” Daud writes at the beginning of the new text. “I realised the power of the written word and sang Hindu songs in Turkish script…By serving Shaykh Zainuddin, evil will be destroyed forever.”

The above passage is an excerpt from a new, painstakingly compiled volume. Chandayan (Maag, 2024). According to linguist Richard Cohen, the translator, the above lines come from a cultural context that can be considered Hindu, in which Sufism was the dominant stream of faith among the elite. ChandayanThe story follows two aristocratic lovers, Chanda and Lorik, whose affair puts them at odds with society and embroils them in a series of adventures. As art historian Naman Ahuja points out in his erudite introduction to the book, lovers’ anguish is a central theme in many of Sanskrit’s great epics: think of Dushyanta and Shakuntala, or Nala and Damayanti.

of ChandayanThe long and winding tale of Lorik is almost certainly borrowed from the wandering Ahir bards and reflects popular tastes. It has battles between dashing heroes, salacious sex scenes, astrologers and prophecies. It has all the elements of a great South Asian romance: a cunning servant, a wronged wife, a hero disguised as a mendicant. But it also contains more subtle Sufi ideas, which require the teachings of a master to understand. The hero, Lorik, is named after the sun, the heroine, Chanda, after the moon. Her maid is named after Jupiter. It is also possible to read the text as a story of the sun and moon becoming one under the aegis of Jupiter. Lorik fights many battles in the text, but they are for increasingly selfless reasons, suggesting the soul’s journey towards God.

As Professor Ahuja writes, Sufis at that time enjoyed widespread support from communities of both Hindu and Islamic traditions. Chandayan It was intended to be a good story-teller, with more esoteric content, for those who had been initiated into Sufi faith. Many of the great Indian epics, Hindu Ramayana, MahabharataJainism Prabandhachintamani,Buddhism Jataka– They also began as folk legends, which were later treated aesthetically and philosophically by priests, poets and Brahmins. Chandayan When it comes to popular ballads, Indian Sufis followed Indian Hindu, Buddhist and Jain precedents quite closely. This is groundbreaking for understanding medieval Islam in general and raises many interesting questions.

Read also: How the Buddhists were defeated by the Brahmins at Nalanda. Even before the Turks came.

Sufis and Yogis: Competition and Translation

Just as there were many schools of Hinduism in India, there were many schools of Islam in India. Chandayan It was popular among Chishti Sufis, who were popular in Delhi and Ajmer. The Chishtis had limited political ambitions. Elsewhere, Sufi leaders had political ambitions and did not hesitate to use violence to obtain them.

at the same time, Chandayan At the same time that the epics were being written in the Ganges, a lineage of uncompromising Iranian Sufis emerged in Kashmir, who had little interest in the local epics and instead focused on converting yogis. They converted temples into Sufi and mosques, sometimes violently. But as I have pointed out in previous columns, they presented their conversions as the result of arguments and magical contests that proved the superiority of their tradition over the other. At least rhetorically, this was reminiscent of the tone of earlier debates between Buddhists and Brahmins. After the Brahmins gained the upper hand, Brahmin texts often presented Buddhists as false heretics who had been incorporated into their superior tradition, just as the Sufis had done with the yogis.

However, other schools of Sufism have looked to the yoga tradition for inspiration and ideas. The Refraction of Islam in India: The Place of Sufism and YogaHistorian Karl W. Ernst has documented many examples, especially in Bengal and the Punjab. In Bengal, for example, the Tantric yogic view of the body was the basis of much Sufi literature, including the chakras and the nectar of immortality. In the Tantric tradition, there are seven chakras in the body, each associated with a deity. Sufis viewed the chakras as mystical places, and placed angels in the place of deities.

In fact, Sufis and yogis had much in common: both used breathing exercises and chanting for spiritual experience, both recognized no caste distinctions, both were buried rather than cremated, and wandering yogis stayed in Sufi monasteries. Dargahand both traditions exchanged not only ideas but also stories. refraction, According to a report collected by Ernst in 1998, the yogis of Gorakhpur claimed that the Prophet Muhammad was a Nath Yogi. Claiming the founders of other religions as members of one’s own is quite a tradition in South Asia. Vishnu worshippers claimed both the Buddha and the Jain teacher Rishabha as incarnations of their god. For example, the 16th-century Sufi master Muhammad Gaut Gwarili, in his Persian translation of an Arabic translation of a Sanskrit yoga text, claimed that Gorakhnath was the Islamic prophet Khizr.

Read also: Kashmiris brought Buddhism to the West, and Mongol rulers brought it to Iran.

Islam in India

Gwariyari text, Bahr al-Hayatis notable in many other respects as well; in one passage he invokes the tantric goddess Kamakhya to articulate certain yoga postures. His works were composed in Gujarat and spread to the Deccan, Mecca, North Africa, Turkey and Indonesia. Indian Sufism, itself made up of many different traditions, was a unique and powerful entity within the wider Islamic world.

His involvement with Sanskrit language and folk traditions was not a one-off. Lives of Rajput QueensHistorian Ramya Sreenivasan says: PadmavatThe 16th-century Sufi text that inspired the 2018 Bollywood film. Padmavat The film is based on an oral legend about Alauddin Khilji, the Sultan of Delhi, who is portrayed in Bollywood as a half-mad barbarian. Padmavat Originally, Khilji was used as a metaphor for worldly illusion, while Rani Padmavati, the untouchable object of his desire, was a symbol of wisdom.

Such absurd misinterpretations of Indian Muslim history have become all too common. Indian liberals have tended to gloss over the violence associated with kingship, and have even romanticized the Mughal kings in particular. Jodha Akbaror Mughal-e-Azam). This view has now been replaced by a far-right myth based on a few palace documents written by bigoted immigrants that all Indian Muslims are foreign, genocidal invaders.

But regional linguistic traditions reveal a vast Indo-Islamic world firmly rooted in Indian mythology and tradition. Indian Muslims engaged with folk traditions in the same way that Buddhists, Brahmins, and Jains had once done. In many cases, they shared the same Gods as Hindus. Like all Indian religions, Islam has contested and fought violently with others. And when backed by royal power, Indian Muslims may have been as wicked as Indian Hindus or Indian Buddhists. But medieval rhetoric is no justification for contemporary policies. In tolerance as in occasional persecution, throughout history, Indian Muslims have been as Indian as we are.

Anirudh Canisetti is a public historian. He is the author of Lords of the Deccan, a new history of medieval South India, and host of Echoes of India and the Yuddha podcast. Follow him on Twitter: @AKanisetti. Opinions expressed are personal.

This article is part of our series, “Thinking the Middle Ages,” which delves deep into medieval culture, politics and history in India.

(Editing by Zoya Bhatti)

Read the full story