Researchers observed that in workplaces where employees at high risk for cardiovascular disease had more control over their time and work, cardiometabolic risk was reduced.

Immediate release: November 8, 2023

BOSTON, MA—Increasing workplace flexibility may lower the risk of cardiovascular disease for certain employees, according to a new study led by Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health and Pennsylvania State University. . In workplaces that have implemented interventions aimed at reducing conflicts between employees’ work and personal/home lives, employees with higher baseline cardiometabolic risk, especially older employees, are more likely to have cardiovascular disease. Researchers observed a reduction in risk equivalent to 5 to 10 years. Age-related cardiometabolic changes.

The study was published Nov. 8 in The American Journal of Public Health. This is one of the first studies to assess whether changes in work environment affect cardiometabolic risk.

“This study shows that working conditions are an important social determinant of health,” said co-first author and Thomas D. Cabot Professor of Public Policy and Epidemiology at the Harvard Chan School of Public Policy at Harvard University. said Lisa Berkman, director of the Population and Development Research Center. “We found that reducing stressful work environments and work-family conflict reduces the risk of cardiovascular disease among more vulnerable employees, without negatively impacting productivity. ‘s findings may have particularly significant implications for low- and middle-wage workers, who traditionally have less control over their schedules and job demands and where health inequalities are more acute.

As part of the Work, Family, and Health Network, researchers designed a workplace intervention aimed at increasing work-life balance. Supervisors were trained in strategies to demonstrate support for employees’ personal and family lives, alongside their employees’ work performance. Employees) participated in hands-on training to identify new ways to give employees more control over their schedules and tasks.

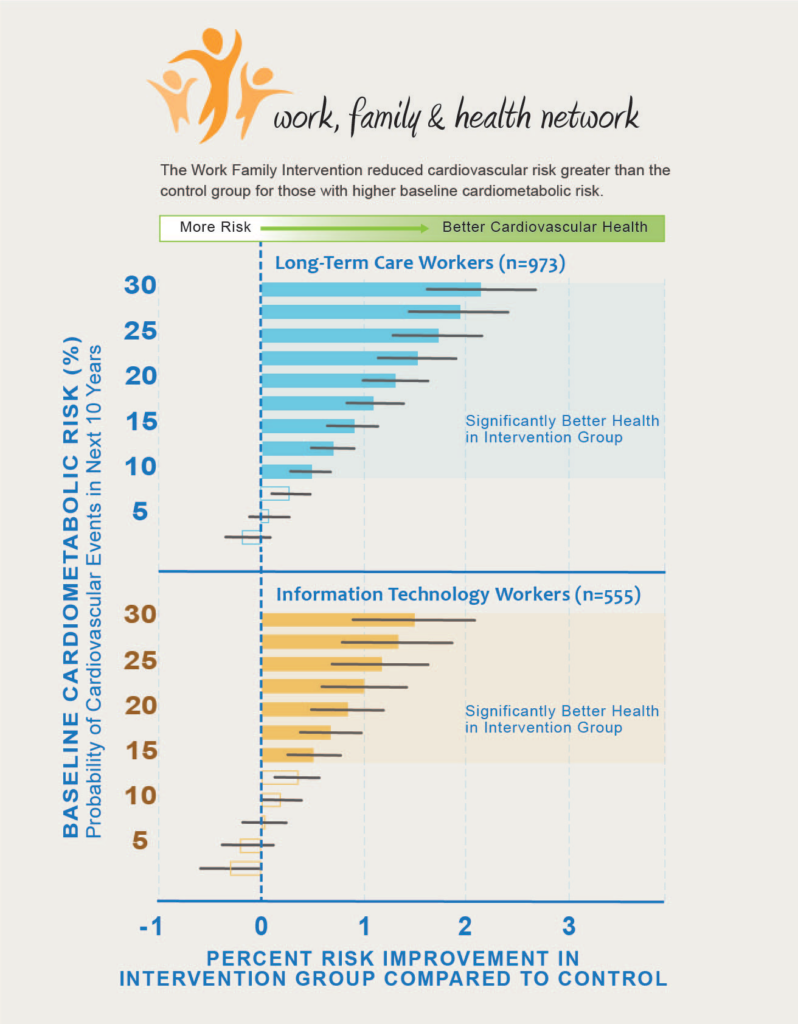

Researchers randomly assigned the intervention to work units/sites within two companies: an IT company with 555 participating employees and a long-term care company with 973 participating employees. The IT workforce consisted of male and female high- and medium-paid technical workers. Long-term care staff consisted primarily of female, low-wage direct caregivers. Other units/sites were not assigned interventions and therefore carried out business as usual.

These 1,528 employees in the experimental and control groups also had their systolic blood pressure, BMI, glycated hemoglobin, smoking status, HDL cholesterol, and total cholesterol recorded at the beginning of the study and 12 months later. The researchers used this health information to calculate each employee’s cardiometabolic risk score (CRS), with higher scores indicating a higher estimated risk of developing cardiovascular disease within 10 years.

This study found that workplace interventions did not have a significant overall impact on employees’ CRS. However, the researchers observed a decrease in CRS, especially among employees with high baseline CRS. Employees at IT and nursing care companies experienced a decrease in CRS equivalent to an age-related change of 5.5 years and 10.3 years. Each. Age also played a role, with employees aged 45 and older with higher baseline CRS more likely to experience attrition than younger employees.

“This intervention is designed to change workplace culture over time with the aim of reducing conflict between employees’ work and personal lives and ultimately improving employee health.” said co-lead author Orpheu Buxton, professor of biobehavioral health and professor of biobehavioral health. Penn State University Sleep, Health, and Society Collaborative Laboratory. “We know that changes like this can improve employee health and should be implemented more widely.”

Koga Hayami, a postdoctoral fellow at Harvard University’s Center for Population and Development Research, is also a co-author.

Funding for this research came from the National Institutes of Health (grants U01HD051217, U01HD051218, U01HD051256, U01HD051276, R01HL107240, and U01AG027669) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (grants U01OH008788 and U01HD059773). Additional funding was provided by the University of Minnesota College of Arts and Sciences, the McKnight Foundation, the William T. Grant Foundation, the Alfred P. Sloan Foundation, and the Administration for Children and Families.

“Employee Cardiometabolic Risk After a Cluster-Randomized Workplace Intervention with Work, Family, and Health Networks” Lisa F. Berkman, Erin L. Kelley, Leslie B. Hammer, Frank Miazuwa, Todd Bodnar, Tay McNamara, Hayami K. Koga, Soomi Lee, Miguel Marino, Laura C. Klein, Thomas W. McDade, Ginger Hanson, Phylis Moen, Orfeu M. Buxton, The American Journal of Public Health, November 8, 2023. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2023.307413

Visit the Harvard Chan School website for the latest news, press releases, and multimedia products.

Image: iStock/Nutawut Somsuk

For more information:

maya brownstein

mbrownstein@hsph.harvard.edu

Sarah Lajeunesse

sdl13@psu.edu

###

Harvard University TH Chan School of Public Health brings together passionate experts from many fields to educate a new generation of global health leaders and generate powerful ideas that improve the lives and health of people everywhere. As a community of leading scientists, educators, and students, we work together to bring innovative ideas from the lab into people’s lives, making not only scientific advances, but also personal action and public policy. , also working to change medical practice. Each year, the Harvard Chan School has more than 400 faculty members who teach more than 1,000 of her full-time students from around the world and train thousands more through online and executive education courses. Founded in 1913 as the Harvard-MIT School of Health Officials, the school is known as America’s oldest professional training program in public health.