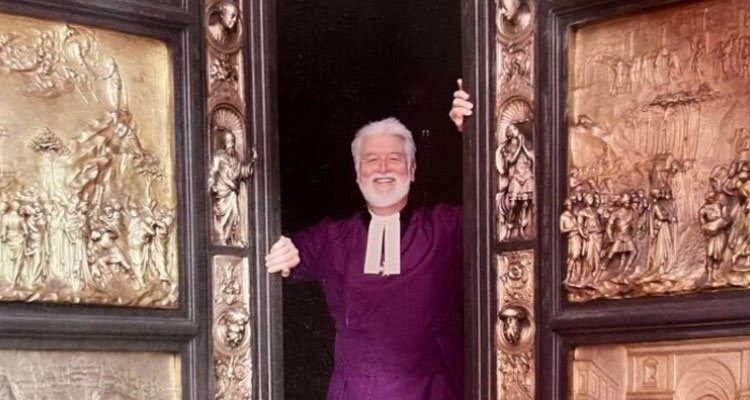

One of our most charismatic deans, Alan Jones, flourished at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco, and the Cathedral flourished with him. Alan passed away on January 14 at the age of 83. To me, he was an attentive mentor, a fun conversationalist, and just a great boss.

My interview with Alan Jones in 2004 was unlike any other. At the start of the interview, before the tea was even poured, he asked me, “Jeffrey, do you know Palestrina’s Creed? Mass Cine NomineeDespite Alain’s persistent gaze, I thought it was a trick question and refused. However, Alain explained that he had programmed a loop of the verse that connects “et sepultus est” and “et resurrexit” to accompany his daily yoga.

The fusion of Palestrina and yoga was typical of Alan. “To be an American is a complicated destiny,” Henry James wrote, “and one of the responsibilities that comes with it is to combat a superstitious appreciation of Europe.” Born in London, Alan adopted the openness and extroversion of the American people. He was unsentimental about England and dispassionate about the Church of England. But he often despaired at American ignorance of history and the relentless narcissism of our culture.

He was a man of contrasts in teaching and style. Alan’s writings and sermons are not for those who want a quick confirmation of preconceived ideas and official dogmas. His complaint is that people think they think, but in reality they are just sorting out their prejudices. Alan’s “rethinking” of Christianity is actually more Christocentric and more sacramental than most San Francisco believers prefer. But he was not dogmatic or partisan. There was laughter in staff meetings when he suggested that if Grace Cathedral were converted into a church cathedral, the church would become a church cathedral. Truly diverseThe next clergyman Britain hires should be a Republican, a Texan and a father of four. “The Englishman always draws the line unambiguously,” Churchill quipped. Some found Alan Jones’s vagueness infuriating, but it was never boring.

He always insisted on the unique and complex mission of the cathedral as distinct from that of larger dioceses. He was a progressive traditionalist. He was an enthusiastic attendee of daily worship, something that was at odds with the clerical culture of the time. Alan’s understanding of the liturgy, shaped by his experiences at Mirfield, Lincoln Theological Seminary and the General Seminary, was fundamentally Anglo-Catholic. This was very encouraging to the musicians.

Alan sang at the 1953 coronation and his playlist included Walton’s Te Deum I listened to a lot of Vaughan Williams. I also liked Tallis in the Dorian mode. Alan and I devised a yearly program of poetry and organ improvisations. He looked forward to hearing the major works of Messiaen. I guaranteed opera performances for the choir and went to an annual choir camp. The modulated rhythms in his sermons were essentially musicalThe overall structure of his sermons and their relationship to anecdotal details were symphonic. Sometimes he preached like an opera, and sometimes we needed more than that. “The sacred cannot be expressed in words,” he said. “That’s why we sing so much.”

Alan was a great leader. He was a good administrator and learned to delegate, but his senior staff colleagues sensed that he took a genuine interest in his department, preferred to ask questions rather than preemptively answer, and was willing to learn from those “below” him.

I learned a lot from Alan, often unwillingly, and the most important of those lessons was to slow down when in a hurry. Festina LenteIn a large and complex facility like Grace Cathedral, improvements were often hard won. Another of Alan’s mantras was, “Who needs to be there when we discuss this issue?” I appreciated his boundless humor, often used to ward off the storm clouds ahead. We had a “hymn intervention” on Sunday mornings. Alan “spontaneously” interrupted the hymn to encourage the timid congregation to try again, but this time “with enthusiasm, pretending to be Methodists”. For a 6’4″ tall, imperious English priest, this was surprisingly informal. Using the shock factor, he appeased the congregation and pleased everyone.

Like many talented leaders, Alan’s charisma attracted some people negatively. Some felt threatened by what he had built, the friendships and influence he enjoyed. There were certainly aspects of what he called “going with the traffic” that may have contributed to his over-inflated public image.

But Alan changed lives from the pulpit in the cathedral. One December, he included a surprise in his sermon at midnight mass that only the four of us knew about. Alan spoke about Irving Berlin losing his young son on Christmas Day. Then, from the far pews, a lone treble choir sang “White Christmas” unaccompanied, while a priest on the catwalk rained stage “snow” on the nave. There were gasps of amazement and smiles all around. This was Anglicanism, San Francisco style. It was Palestrina and yoga. And few in attendance will have forgotten it.

It’s tempting to dismiss the “White Christmas” episode, as I did before my conversion, as manipulative nostalgia and unwelcome pretense. But Alan Jones was attuned to the darker side of institutions and the individuals who ran them. A naturalized American, he was vulnerable about his own failings and loopholes. Nostalgia, he felt, could point the way to something deeper within, and it takes music to melt a cold heart. Alan, Hurtful JoyAbout the thing that is most important to us, and when we neglect it, it becomes our problem: our longing for God’s love. Qantas Films It unfolds contrapuntally through pain and alienation. In the words of Wendell Berry, Alan often exhorted us to “rejoice, even considering all the facts.”

May his memory be a blessing.

Jeffrey Smith is Professor of Organ and Sacred Music at the Indiana University Jacobs School of Music. From 2004 to 2009, he served as Music Director at Grace Cathedral in San Francisco.